Written by Mark DePaolo, DVM. COPYRIGHT © 2012 All rights reserved.

What Are Internal Parasites?

Horses share a symbiotic relationship with several varieties of internal parasites. In small numbers, this relationship is both normal and healthy. The parasites gain a host that enables them to mature and perpetuate their life cycle, while the horse obtains a measure of resistance to further parasitic infection. However, in large numbers, internal parasites pose a serious risk to a horse’s health. These parasites include ascarids (round worms), large and small strongyles (blood worms), tapeworms, bots, pinworms, stomach worms, neck threadworms and lungworms. Each parasite has its own unique infection pattern, health implications and treatment protocols. The sheer variety is dizzying and can make parasite management seem a daunting task.

In North America, four parasites pose the greatest risk to a mature horse’s health:

- large strongyles

- small strongyles

- tapeworms

- bots.

Ascarids (round worms) are a concern in horses under the age of two, yet most foals develop immunity after about eighteen months. The two most prevalent parasites are large and small strongyles. In excessive quantities these worms can cause colic, weight loss, fever, poor coat, anemia, as well as threaten the health of arterial walls and blood vessels.

Symptoms of parasite infestation include:

- Weight loss

- Poor hair coat

- Colic

- Dermatitis

- Chronic Tail rubbing

- Respiratory Issues

- Poor wound healing

Types of internal parasites include:

Ascarids (Round Worms): These are the largest of the parasites, growing to as long as one foot. They are most common in foals and many horses develop immunity by the age of eighteen months. These worms are linked to cold, fever, loss of appetite, decreased weight and susceptibility to pneumonia.

Large and Small Strongyles (Bloodworms): The two most prevalent worms affecting horses over the age of two in North America. Small strongyles are more difficult to eradicate because they encyst in the digestive lining, where they can remain dormant for years before maturing and laying eggs. This also makes them immune to most dewormers until they emerge from they protective cysts. These parasites cause colic, weight loss, fever, anemia, and deterioration of the arterial walls and blood vessels.

Bots: Bot eggs laid by female bot flies on a horse’s legs, then are ingested and attach to the stomach walls where they mature until they pass into an untreated horse’s manure. Once in manure on the ground, they hatch and develop into adult flies. These parasites are not worms, but are responsible for ulcers and perforations of the stomach wall.

Tapeworms: An increasing concern, especially for horses in the East and locations like Michigan and Wisconsin, these parasites can grow to four feet in length and are linked to increased colic – specifically spasmodic (gas-induced) colic.

Pinworms: Though fairly uncommon, pinworm eggs are sticky and can cling to stall walls and other surfaces. These parasites are can cause severe itching especially of the anus.

Stomach Worms: These parasites reside in the stomach where they lay eggs that are passed through to manure where they adhere to host maggots. When the maggots develop into flies and land on open wounds, worms are deposited that can cause irritation and impede healing.

Neck Threadworm: Transmitted by gnats, these parasites live in tendons and ligaments, and are associated with severe dermatitis.

Threadworm: A parasite that typically only affects foals, the threadworm can cause severe diarrhea and damage to intestinal lining. Horses typically achieve immunity after six months of age.

Lungworm: These parasites travel to the airways via the blood stream and can cause respiratory issues and an overall deterioration in health.

How Did My Horse Get Worms?

Parasites are an inescapable presence in modern horses. Historically horses free grazed on open pasture, rarely returning to the same location within a year or grazing in close proximity to manure. Today’s horse leads a considerably more confined existence, eating in the same locations and in close proximity to manure. In such settings, the normal symbiotic relationship can spiral into a parasite overload with significant health consequences.

Horses are infected with large or small strongyles when eggs are passed in an infected horse’s manure. Given the proper conditions, these eggs then hatch to larvae and adhere to grass or are shed in water where they are consumed by other horses. The eggs passed in manure do not infect horses; instead they must hatch and mature through three stages before they are ingested to establish an infection.

Animals living in pastures, corrals and fields are more prone to high parasite burdens, as their environment is not as carefully maintained as those who live only in stalls. Performance horses kept in stalls typically see their bedding cleaned daily and replaced regularly. Such maintenance reduces fecal contact and exposure to parasite eggs, minimizing the risk of high parasite burdens. Moreover, stall-bound horses live a comparatively isolated life and are typically only exposed to their own manure -- again reducing exposure to parasite eggs shed from other animals. Horses kept primarily in stalls can still exhibit high parasite burdens, but their risk is typically less than pasture kept horses because effective management is usually much easier.

Pasture kept horses come into contact with manure more regularly, as it is often difficult and costly to pick an entire field on a regular basis. As a solution, many people resort to dragging manure piles across pastures. Manure piles should never be spread across fields, as this essentially distributes parasite eggs over the entire area. Regular manure removal is a healthier option. This will reduce the risk of excessive parasite exposure, but pasture-bound horses typically require more monitoring and care to maintain low parasite levels.

How Does Traditional Medicine Treat Parasites?

Given the reuse of pastures and close proximity to manure, increased exposure is inescapable for the modern horse. As such, responsible owners have long been advised that aggressive, periodic deworming is essential to controlling parasite levels and maintaining a healthy horse.

Before the 1960’s deworming required a veterinarian to pass a stomach tube through the horse’s nose to introduce powerful chemicals that killed any and all parasites. The process was difficult, time consuming and costly. Veterinarians always took a fecal egg count (FEC), to ensure the ordeal was necessary. In the decades since, over the counter paste dewormers simplified the process and allowed owners to conduct their own parasite management.

Today’s typical approach varies little from the recommendations established 30 years ago – purge deworming through the administration of a paste dewormer every six to eight weeks or rotational deworming through the use of two or more different purge dewormers at set intervals. Continuous dewormers that are added to daily grain rations, like Strongid C, are also common. However, manufacturers of continuous dewormers now recommend supplementing their products with paste dewormers biannually to effectively control small strongyles and tapeworms.

Typical parasite treatments include:

Quest®: Containing Moxidectin, this paste dewormer is effective against large and small strongyle (including encysted small strongyles) , pinworms, lungworms and ascarids.

Ivermectin, Zimectrin®, Equimectrin® and Bimectin®: These paste treatments contain a drug generically known as ivermectin and are effective against large and small strongyles, pinworms, ascarids, stomach worms, bots, lungworms and threadworms.

Safe-Guard® and Panacur®: These paste medications contain fenbendazole, which is effective against large and small strongyles, pinworms and ascarids. Versions like Safe-Guard Power Dose and Panacur PowerPak are designed to be given over a period of successive days to eradicate encysted small strongyles.

Strongid™ P, Rotecin P and Exodus Paste: Paste dewormers containing pyrantel paomate, these medications are effective against large and small strongyles, pinworms and ascarids.

Equimax®, Zimecterin® Gold, Anthelcide EQ and Benzelmin Anthelminitic: These paste dewormers contain both ivermectin and parziquantel, which is effective against tapeworms.

Strongid™ C, Strongid™ C2X with Equimax®, Continuex® and CW®: These continuous dewormers are fed daily along with a horse’s grain as a preventative approach to parasite infestation. They are effective against large and small strongyles, pinworms and ascarids.

What are the shortfalls of the traditional approach to de-worming?

As with many medications, a rising concern with dewormers lies in drug resistance. Over the past thirty years, the ease and availability of paste dewormers has vastly increased the number of horses that receive treatment at regular intervals. During this time, resistance to various treatments has become widespread.

The continuous dewormer approach is also problematic. Preventative treatment through daily dewormers, though appealing, involves regular exposure to medications and small amounts of toxins. This distracts the immune system from doing its indended job because it is busy combatting these low levels of poison.

Each year more and more farms are diagnosed with “superworms” resistant to many of the standard deworming products. Some veterinarians and daily dewormer manufacturers are recommending using both a daily oral deworming supplement in conjunction with quarterly paste dewormers.

Continued use of paste purge dewormers on a set schedule and continuous daily dewormers, regardless of contamination levels, will lead to more resistance and a lack of effective products as well as being detrimental to your horse's health.

The use of paste dewormers on an established schedule also fails to effectively tailor treatment for each individual horse. Inevitably, some horses are “wormier” than others. Issues such as genetics, immune deficiency and overall health can affect a horse’s susceptibility to internal parasites.

The one-size-fits–all approach of purge deworming with paste products and continuous dewormers ignores these individual differences. This is especially troublesome as a complete and total purge of parasite populations is not beneficial. In small numbers, the symbiotic horse/parasite relationship is healthy. The horse manufactures antibodies to the parasite to keep levels low and the worms have a place to live and reproduce. For horses with low parasite burdens, scheduled treatment with purge paste dewormers can actually reduce parasite levels to unhealthy lows.

In addition to the risk of resistance, such a broad-based approach unnecessarily exposes horses with low parasite burdens to harsh chemical treatments. As implied by their name, purge dewormers use chemicals to kill off parasite populations. This means every six to eight weeks horses are exposed to low-grade poisons – whether or not they carry a high parasite burden.

Unnecessary exposure to poisons, no matter how small the level, is less than ideal. It is not uncommon for horses to have small reactions to synthetic paste dewormers varying in severity from swollen glands and skin reactions to colic and laminitis. Anecdotal evidence has even linked the most powerful purge dewormers, like Quest®, to severe health issues and even death as some horses struggle to eliminate massive dead worm populations at once. Ivermectin which has demonstrated great longevity and effectiveness against parasites, can also have adverse effects when used too frequently or in large doses.

A 2009 study Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association study detailed severe neurological reactions in three Quarter Horses after receiving an ivermectin paste. The horses experienced depression, lack of coordination, impaired reflexes and muscle twitch. Despite treatment, one animal had to be euthanized. After all considerations, dewormers are still toxic chemicals and should be used only when needed.

How do I determine if my horse has worms?

Paste dewormers have their place and are still occasionally necessary to maintain a healthy horse. However, it is important to reevaluate their use and avoid scheduled administration without knowledge of a horse’s specific parasite burden.

The most important step owners can take in parasite management is a simple fecal egg count (FEC). Before paste dewormers became customary, parasite management always began with a FEC to determine if treatment was necessary. Reintroducing this small step can reduce drug resistance, increase effectiveness and minimize exposure to harmful chemicals by only treating horses with high parasite burdens. Instead of blindly administering paste dewormer every six to eight weeks, simply administer FECs at similar intervals.

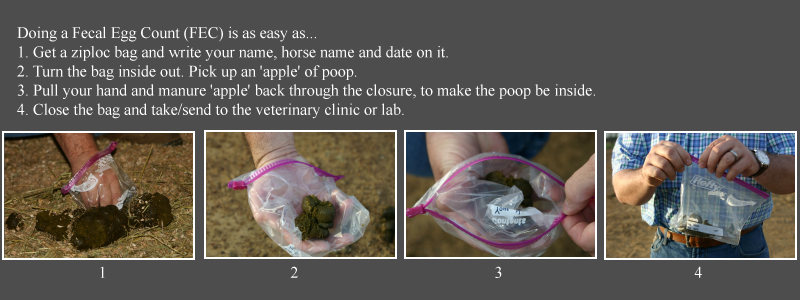

Nearly any veterinarian, including small animal practices, can conduct an FEC and will typically charge as little as $15 to $25. Simply collect a small, fresh manure ball in a sealable bag marked with the date and horse’s information. The vet clinic will normally compile a report within twenty-four hours. This report will not only determine the number of parasite eggs in the stool sample, it will enable strategic deworming by also identifying what types of parasites are present. Armed with this information, caregivers can make an informed decision as to whether or not to deworm and the best dewormer to use for the specific infestation.

If an FEC indicates the presence of more than two hundred eggs per gram, the horse should be dewormed with the mildest medication available that specifically targets the parasite in question. If less than two hundred eggs per gram are found, a follow-up exam should be conducted in sixty days to verify results and make certain that the initial test wasn’t conducted during a point in the parasites' life cycle where eggs are not present. After a few rounds of FECs, caregivers can typically identify “wormier” horses and those that rarely carry a high parasite burden. For many low-burden horses, FECs can be reduced to an annual, or even less frequent, affair.

Perhaps most importantly, FECs provide enough information for targeted treatment and the elimination of overly harsh products like Quest® and PowerPak®. By knowing the level and type of parasite infestation, more benign medications like Strongid, Panacur or Safe-Guard can be employed. The benefits of using these alternatives are immeasurable, as Quest® is so powerful that consuming manure from treated horses can kill certain breeds of dogs. Any opportunity to reduce a horse’s exposure to such harsh medications is invaluable.

Although this extra step in parasite management may appear to increase health care costs, FECs can create savings by reducing frequent and unnecessary deworming treatments. With good horse keeping protocols, FECs can be run as little as once or twice a year and can reduce the need for paste dewormers to once a year or less, providing a better overall horse health and a cost savings.

Are there alternatives to the traditional de-worming approach?

In addition to traditional paste dewormers and continuous dewormers, there are a few natural or holistic alternatives to chemical parasite management. One of the most popular natural approaches involves products with diatomaceous earth, a naturally occurring chalky rock consisting of fossilized remains called diatoms. In industrial settings, diatomaceous earth is used as a filtering and absorbing agent and many believe it can filter and eliminate harmful pests like bacteria and protozoa. Proponents of this approach also claim that diatomaceous earth's abrasive qualities can eliminate worms by damaging their outer membranes. These claims are difficult to evaluate and one must consider the possible effects of mild abrasion to the horse's internal organs as well.

Other common holistic treatments include anti-parasitic herbs such as grape seed, pumpkin seed, sage, thyme or wormwood. Many years ago, tobacco was even considered a viable holistic treatment. The primary issue with these approaches lies in the sheer volume required for effectiveness. Large quantities of seeds and certain herbs can produce serious health issues, including increased risk of colic. Of course modern treatment recognizes that tobacco in large quantities can be harmful to health. Grape seed and pumpkin seed can also be problematic, as they have been linked to diarrhea, colic and laminitis in large quantities. Wormwood, the primary ingredient in absinthe, should also be carefully evaluated as it has been associated with kidney, liver and nervous system damage in high doses.

While some holistic approaches may provide an alternative to paste dewormers, their use must be carefully monitored. A natural approach is always admirable, yet many of these treatments fail to provide effective treatment and must be prudently evaluated. Natural remedies are not subject to the same testing and advertising standards as chemical dewormers, so their effectiveness and the veracity of their advertising claims can vary widely. As with all parasite treatments, FECs are still critical to determining a horse's parasite load and the foundation of an effective deworming protocol.

Tips for natural de-worming:

-

Internal Parasites are a natural and healthy presence in horses in low levels.

-

Excessive parasite levels can cause serious health issues and must be reduced.

-

Traditional deworming principles have changed little in 30 years and are flawed.

-

Overuse of paste dewormers has increased the risk of drug resistance and ignores the fact that 20% of horses in a given population are responsible for 80% of parasite eggs shed in pastures and stalls.

-

Natural alternatives are available, but must be approached carefully interms of effectiveness and safety.

-

Fecal Egg Counts (FECs) should always be conducted to determine the need for deworming medication.

-

An FEC can identify “wormier” horses and allow the use of medications that specifically target a given parasite infection.

-

Although an extra step, FECs will not significantly increase the cost of horse care and can reduce exposure to harsh chemical treatments – preventing reactions to synthetic dewormers and minimizing the risk of drug resistance.

This information is for educational purposes only and should not be considered as Dr. DePaolo diagnosing your horse’s health. DePaolo Equine Concepts, Inc. recommends that you consult your regular veterinarian regarding specific health concerns.